Wrapping up WCRI’s opt out marathon, a four-person roundtable dove into the issue with AIA’s Bruce Wood leading off. Bruce began with something I kept thinking during the earlier talk: what problem is opt out solving?

Work comp rates are down, no systems are in crisis, benefits are decent and in many states improving, and medical costs are, with a couple notable exceptions, not increasing too much.

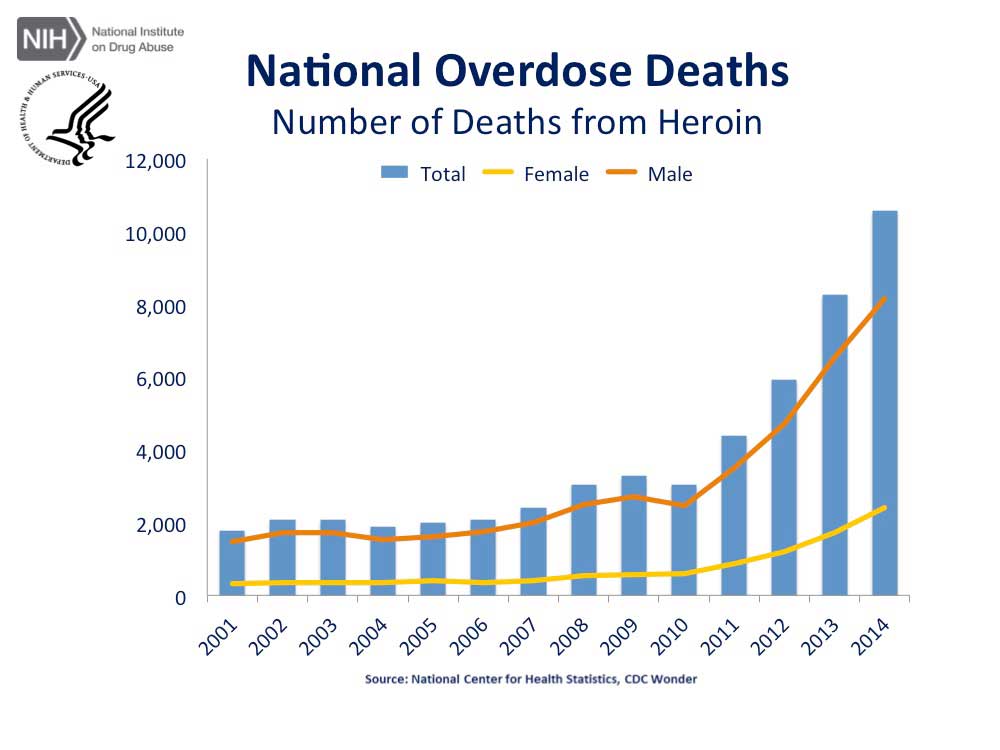

Yes, there are problems in many states, some much worse than others – opioids, crappy docs, too much litigation, some outright lousy incentives that motivate bad behavior, and some bad employers, but overall, we’re doing ok.

Bruce went thru a litany of reasons opt out isn’t viable or appropriate; as one of the nation’s most knowledgeable experts on all states’ systems, he knows of what he speaks. One key point is that opt out is a federally regulated plan, therefore states can’t require financial stability or standards or minimums or audits. Thus, even if states pass laws requiring financial standards, guarantee funds, etc, these laws will not apply to opt out.

Next up Elizabeth Bailey of Waffle House gave her views; the covered-smothered-chunked-and-served company is a non-subscriber in TX and insured thru the work comp system in OK. For those unfamiliar with WH, they sell waffles and related foodstuffs in sort of a mini-diner setting. WH opted out in TX because the system was broken back in 2002; Bailey indicated that the lack of settlement ability and lifetime medical benefits coupled with the strength of providers made the TX WC system untenable.

That’s worked out pretty well – according to Bailey their plan features solid benefits, the ability to direct to specific medical providers, a strong focus on workplace safety have delivered much lower costs due to a dramatically lower injury rate, almost no indemnity expenses, and an overall decrease of almost 90% in costs.

My based-on-almost-no-real-knowledge-of-WH’s-program view is these folks are doing things the right way, which benefits their workers greatly – far fewer have injuries, which is the core goal of any occupational program. And they get back to work quickly, so they don’t get stuck in a disability mindset.

Attorney Alan Pierce then weighed in; his slides were very detailed (much better for future reading than trying to follow live). Perhaps his key point was the contention work comp is a right, not a benefit; a right owned by the employer.

Aside – Pierce’s pontification was more than a bit annoying; his attempt to denigrate the sessions and attendees by asserting that there were few/no injured workers in the audience, and therefore he, as an “injured worker advocate” was somehow uniquely qualified and special. A physician friend and colleague noted afterwards that this was offensive indeed as there were several treating docs in attendance, all of whom likely had just as much experience “advocating” for injured workers.

Pierce made a case that opt out results in a dramatically greater cost shifting. While I don’t agree with all the examples of potential issues, he made a reasonable case that opt out may well increase cost shifting of both medical and wage replacement expense away from the employer.

The session wrapped up with a representative from the Oklahoma Insurance Dept, James Mills. He provided a concise overview of the program, which is regulated much more tightly than Texas’.

The key takeaway is one offered by…once again…David Deitz MD. There just isn’t enough data, or, arguably, any data that would allow anyone to make a reasonable assessment of opt out and/or a comparison with workers’ comp.

Until and unless there is, it is difficult if not impossible to evaluate opt out.