Here’s what happened last week…

People who enroll in exchange programs in red states pay 3.2 percent more for their health insurance than folks in purple or blue states. Research indicates it is because fewer folks in red states sign up for coverage – and these are likely the healthier people.

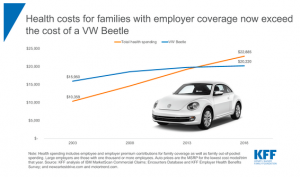

Families pay about a third of their healthcare costs, with employers picking up most of the rest.

In part that may be because healthcare now costs more than a new car…Yet one more straw on that poor camel’s back…

Yet another indicator that the healthcare market continues to rapidly consolidate came last week with news that Tufts and Harvard Pilgrim look to be merging.

A you-should-definitely-read-this piece from Harvard Business Review reminds us that variations in data should be considered thru the lens of statistics, not emotion or intuition. An excerpt:

Sorting out variation provides needed context, points to opportunity, and helps managers maintain their cool when something goes wrong. Managers should learn how to measure variation, understand what it tells them about their business, decompose it, and, when necessary, reduce it.

WCRI’s Vennela Thumula PharmD will be discussing Interstate variations in opioid dispensing in a webinar on September 12. Dr Thumula is one of the nation’s leading experts on workers’ comp opioids and well worth your listen. Register here.

Great piece from HealthAffairs on evidence-based treatment guidelines. There’s a lot of nonsense and BS out there – especially in workers’ comp guidelines – and this article provides a solid foundation to understand what’s real and what isn’t. Here’s the central message…

There are two core issues that lead to a host of problems. First, there is a lack of centralized authority to coordinate, vet, approve, and catalog guidelines. Second, there is an absence of a universal methodology to create guidelines—every professional organization promulgating guidelines today generally decides freely which, if any, framework they will use to construct guidelines.

Finally, if you want to understand how to incentivize physicians – and improve your ability to work with them, read this.

take time to develop relationships with physicians. I need to develop trust. I need to convey the why. And then, once we do that, you can begin to move into the how and the what. And then physicians are ready to look at the dashboards to help you move them forward.