A pending CMS rule may lead to major changes in the use of Prior Authorization, changes that would reverberate across all payers – Medicare, Medicaid, group health, Exchange plans and workers’ comp.

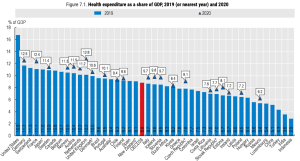

Remember work comp is the flea on the tail of the healthcare elephant:

- WC is 0.7% of total US medical spend and

- a tiny portion of most providers’ patients and

- the draft regs have no exemption for workers’ comp.

The proposed rule is now under review after public comments; there are a wealth of implications and potential issues including:

IT

- requirements re new APIs (electronic links) in PA IT applications including payer and provider interfaces – idea being to streamline flow of information between payers and providers

- payer-to-payer data exchange requirements – essentially linking payers together so a specific patient’s entire health record is kept by its current payer (given patients’ high propensity to switch payers, this will be darn challenging.

- work comp would have to integrate with many other payers...

- build automated processes for providers to determine if a PA is required – idea being to reduce confusion as to what procedures do and do not require a PA

PA processes

- tight time frames for PA processes and possible reduction to 48 hours for expedited requests

- mandatory requirement for payers to include a specific reason for denials

- mandatory reporting for most providers

There’s a lot more to this…I’ve just scratched the surface here.

What does this mean for you?

if you aren’t paying attention to what’s happening in the larger healthcare world, you’re flying blind.

Make no mistake, what CMS does – whether its fee schedules, interoperability requirements, Medicaid eligibility, drug pricing, reimbursement policies, network adequacy or PA changes – affects you.