Medical costs were up a mere 3% in 2014, and actually dropped by a point in 2015 (in NCCI states).

I’ve been in comp a long time, and nothing like this has ever happened. What’s going on?

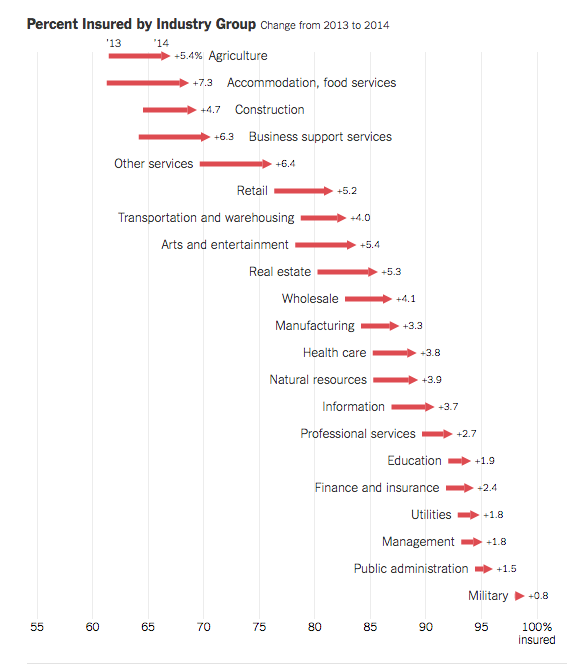

One likely contributor – 20 million more Americans have health insurance, and work comp doesn’t have to pay for medical care for non-injury-related conditions. (Surprisingly, not many of us know that coverage has increased so much…)

If someone gets hurt at work, has comorbidities, and needs surgery, those comorbidities have to be addressed as part of the treatment plan. If the patient has health insurance, that’s what pays for the non-injury conditions. If not, work comp’s on the hook.

Clearly, the more workers with insurance, the less added expense for work comp payers. So, here are my back-of-the-virtual-envelope calculations of the impact of ACA on work comp (a more-qualified researcher needs to do a much more thorough job):

In 2009 – 2010, 81.8 percent of the employed population aged 18-64 had health insurance. By March of this year, 90.3 percent had coverage, a 10.4 percent/8.5 point increase.

Around 150 million people were employed this March; running the numbers, that means about 13 million more workers had health insurance early this year than did six years ago.

At 3.2 injuries or illnesses per 100 FTEs, that’s 416,000 patients. About 84,000 of those patients have more severe injuries, the type that may require surgery, physical therapy, and/or more expensive and extensive medication.

We do not know how much of the moderation in medical inflation can be accounted for by expanded health insurance coverage, but we do know there are around 84,000 folks with pretty significant injuries or illnesses that don’t need work comp to pay for non-occupational conditions.

Another factor – employed people with health insurance are healthier than employed people who don’t have insurance. Sure, there are confounding factors here – how long do they have to be insured to become “as healthy” as folks who’ve had insurance for years, and how much healthier do they get for each year they’ve had coverage. I get all that. And some really smart researcher at NCCI or WCRI or NASI will figure that out (c’mon, people, the race is on!)

What does this mean for you?

We don’t KNOW ACA how much reducing work comp medical costs, but it is very likely a major contributor.