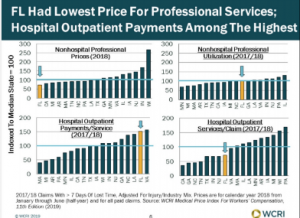

Perhaps the most practical presentation at this year’s WCRI conference focused on outpatient facility costs. While the content itself was excellent, what was more valuable were the implications for medical spend management.

Rebecca Yang PhD provided a wealth of information about outpatient fee schedules, Medicare reimbursement, and the impact of Medicare’s changes on workers’ comp fee schedules. Note that as the slides indicate, findings are preliminary so subject to change.

First, the findings.

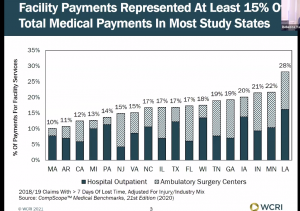

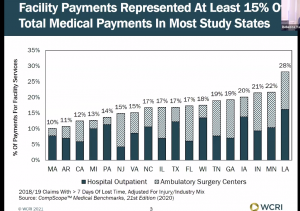

Dr Yang noted that outpatient hospital and Ambulatory Surgical Center costs [outpatient costs] represent about 15% of total medical spend across the 18 study states, with Louisiana the outlier at 28% of spend.

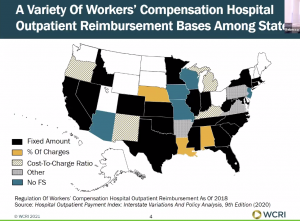

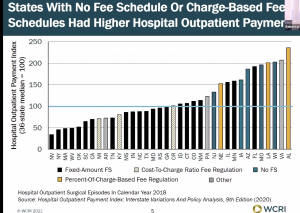

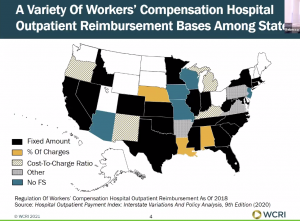

There are lots of different ways to manage spend via fee schedules; one can base reimbursement on a fixed amount, % of charges, cost to charge, Medicare or some hybrid mechanism.

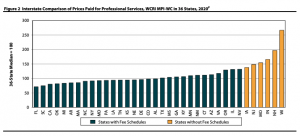

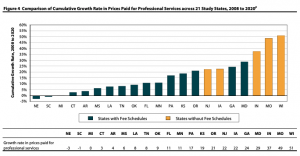

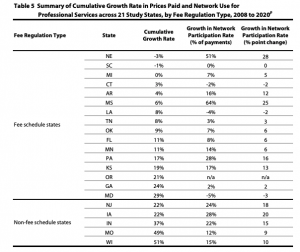

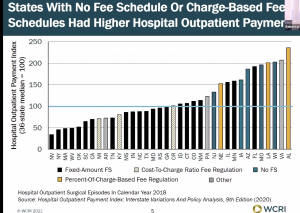

All have strengths and weaknesses, issues and challenges, but – with one very big exception – in general it is better to have a fee schedule than not – except when the fee schedule is easily gamed (we’re looking at you, Florida).

That exception is cost-to-charge, a term describing the ratio between a hospital’s expenses and what they charge. As we’ve discussed here ad nauseam, all hospitals in C-t-C states have to do to make bank is jack up their charges.

I won’t dive deep into details about how Medicare’s changes to reimbursement affect workers’ comp except to note that when the dog wags the tail, the flea on the end (that’s workers’ comp) gets whipped about.

Okay, maybe a little detail…

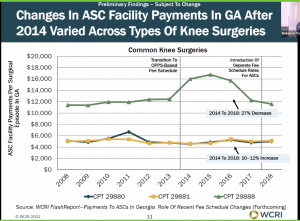

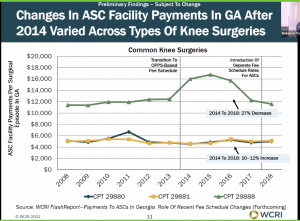

The Peach State adopted Medicare as the basis for the WC FS back in 2013. Essentially, the change followed Medicare FS changes, except excluded device reimbursement and (if I heard this right) some associated charges.

Medicare made changes to its reimbursement in 2016 and 2017 which drove reimbursement declines for some knee surgeries; others were unaffected.

The point of this is to note that basing a fee schedule on a third party’s reimbursement demands payers really deeply fully understand the underlying third party’s reimbursement policies, practices, requirements and nuances.

Most workers’ comp entities don’t. The result is they are unable to ensure medical bills and accompanying documents support reimbursement – or don’t. Far too often, bill review entities just assume everything is in order (if the surgery was pre-approved) and authorize payment for all billed services. Reality is it’s pretty common that some of those billed services should have been bundled into the overall surgical fee.

What does this mean for you?

This isn’t unique to Georgia, or knee surgeries. If your BR operation doesn’t know this stuff at a granular level, you’re probably overypaying.

(WCRI published an excellent summary of outpatient reimbursement and drivers last year).

Oh, and don’t forget my annual Aril Fool’s post is coming up Thursday. Don’t be fooled!